The aim of writing poetry is, for the most part …

- To make money,

- To expose the poet’s thinking and feeling,

- To allow the reader to share the poet’s experience,

- To impress chicks.

Well, if you said, “To make money” you are a true capitalist but somewhat of an idiot. Here’s what John Keating says about poetry in the film, Dead Poet’s Society:

We don’t read and write poetry because it’s cute. We read and write poetry because we are members of the human race. And the human race is filled with passion. And medicine, law, business, engineering, these are noble pursuits and necessary to sustain life. But poetry, beauty, romance, love, these are what we stay alive for. To quote from Whitman, “O me! O life!… of the questions of these recurring; of the endless trains of the faithless… of cities filled with the foolish; what good amid these, O me, O life?” Answer. That you are here – that life exists, and identity; that the powerful play goes on and you may contribute a verse. That the powerful play goes on and you may contribute a verse. What will your verse be?

When I was in college I wrote many poems; I experimented with traditional poetic forms; I even submitted my best work for publication and was rewarded with rejections that said, “Promising.” I suppose I was overly influenced by Wallace Stevens and W. B. Yeats back then but now, whenever I run across one of my old poems in a dusty folder on the closet shelf, it’s almost too painful to read. Where did all that romantic stylizing go? I remember in Graduate School setting aside The Cantos and reading the IBM COBOL manual. I still cringe when I remember that IBM was incapable of publishing anything that wasn’t in ALL CAPS.

Computers brought me a career and now a comfortable retirement, but they also destroyed the poetry in my life.

Every once in a while I read a little poetry, usually in a journal like Tin House or Conjuctions. My subscription to Poetry was traded in for a subscription to Dr. Dobb’s Journal of Computer Calisthenics & Orthodontia just after the fall of Saigon. It was around then that I realized I had become a suit, an automaton, a capitalist. For fun I took part in riding-mower races in the back yards of our development, calculated the savings we were getting with the freezer-plan supplying our meat, and catalogued the bust-sizes of all the wives in the neighborhood.

Back then it was easier to drape myself around our circular couch, watch football games, and sample yet-another-bottle of Jack Daniel or J. T. S. Brown. Upstairs there was a huge California King-Sized bed but where was the romance? When I was first married (the first time) we slept together in a small twin-sized bed, carefully spooning to avoid waking up on the floor. That was also when I read and wrote poetry. I guess that California King is the objective correlative of my life in the ’70s and ’80s. My paychecks were larger, my suits were newer, and the freezer was always full. But no romance.

I began to regain some semblance of being human in the 90s, started reading again, some poetry and some non-fiction, but mostly a relatively new form for me, the novel. I discovered I had very little exposure to American literature and world literature, outside of the major European countries, was an embarrassing hole in my experience … and this from a man who was a strong advocate of what is officially called Comparative Literature.

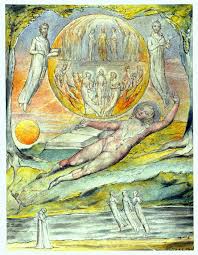

I’m retired now and living alone with my two dogs but I have started reading more poetry and might even pick up a fountain pen and try out a few rhymes (after all, could I be worse than Neil Sedaka?). I read some Milton the other day and a little Keats. I have two or three volumes of Alexander Pope in the library calling out to me. Most of my poetry volumes have gone into my daughter’s library where they can bask in the midst of academia. I’m sure she will lend them back to me. It might be interesting: in my late teens, William Blake was a head-expander and a tough read … now at 67, what will I find if I crack open a copy of The Book of Urizen?

Do they still publish Poetry? Maybe I can renew my subscription: do you think they’ll take me back after all these years?

I have set aside poetry for a long time now. I mostly read novels, but in the last years my favoritism have changed from those authors more interested in philosophy (Hesse, Huxley) to those more in poetry (Nabokov, Camilo Jose Cela, Borges).

I think its time to give it a chance.

LikeLike

Is this the time-honored Form vs. Content debate? I prefer to characterize the issue as HOW something is said vs. WHAT is being said.

We have many authors who write novels that are overflowing with philosophy yet the writing is highly figurative and beats the pants off a host of golden daffodils. Still, it is common to hear of novels of ideas (Thomas Mann comes to mind) but are we to contrast this to novels that are written well, in fact written so well that the ideas are camouflaged by the figurative language and depth of emotionalism inherent in the prose?

And what about authors such as Borges or Barthelme or Cortázar? Do they write of ideas or do they carefully devised prose (or are they just messing with our heads)? Is there a continuum: poetry to figurative prose to novels of ideas to non-fiction?

Remember: it’s all fiction!

LikeLike

Defining poetry is a tough one. Our daughter, when much younger, opined: “Normal writing goes all the way to the end of the page, but poems don’t”. Leaving aside the implication that poetry isn’t “normal writing”, that’s probably as good a definition of poetry as you’re likely to get, I think. In one sense, she was right: prose is in units of sentences, and poetry in units of lines that can cut across sentences. That is the only technical distinction I can think of.

I don’t personally know anyone who reads poetry. Many read novels, but no poetry. And what they understand by poetry is mere doggerel verse. I do not know how this trend can be reversed.

LikeLike

This is much like Terry Eagleton’s definition where he allows that the difference between poetry and prose is that in poetry, the author decides where to end the line whereas in prose, the printer decides.

I like to follow on Ezra Pound’s assertion that “Great literature is simply language charged with meaning to the utmost possible degree” and suggest that poetry is the distillation of great literature.

Rest assured: there is a lot of poetry being published today so I suspect there are still plenty of readers buying it. And, NO … it’s not all doggerel; but with the apparent demise of the more traditional forms of poetry, even the best stuff today can read like highly concentrated prose (but no bongos, please).

LikeLike